Much has previously been said on the Jewish connection to the comics medium and the superhero genre, given that many of the early comics creators were in fact Jewish. In particular, much has been written about Superman, who was created by two Jewish teenagers in Cleveland circa 1938, and also more generally about the Golden Age of comics that followed. Much less has been said about the Silver Age associated with the 60s, and about Marvel Comics which started early in that decade.

So the three movies based on Marvel Comics that were released this past spring, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, The Amazing Spider-Man 2, and X-Men: Days of Future Past, provided an occasion to think about the topic, and then write a think piece on the subject. Here's how it begins:

The second quarter of 2014 has been rather remarkable for superhero movies, with three different films, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, The Amazing Spider-Man 2, and X-Men: Days of Future Past, in the theaters all at the same time at one point.

At this point, it makes sense to include the trailers for the three films, so that even if you haven't seen them, you can at least get a sense of what is being referring to.

Of course, the trailers emphasize action and special effects, but at least you can get a feel for the style of the films from them. But the interest here is in the characters and essential plot lines as they relate to the characters, and how that reflects a certain ethnic and religious experience, and identity. So let us return to the opinion piece now:

All three movies are adaptations of Marvel Comics, the publishing group launched by Stan Lee (aka Stanley Lieber) in 1961, and purchased by Disney in 2009. Stan Lee was the son of Jewish immigrants from Romania, and as a teenager took a job in 1939 with Timely Publications, the company that he eventually would evolve into Marvel Comics.

The Marvel Age, as it came to be known, was in many ways the result of a collaboration between Lee, as writer and editor, and the artist Jack Kirby. Kirby (aka Jacob Kurtzberg), the son of Jewish immigrants from Austria, started to work as a comics artist in 1936, and was hired by Timely in 1940, while he was still in his early 20s. He worked with Joe Simon, just a few years his senior and also the son of Jewish immigrants, and the two created the most famous of patriotically-themed superheroes, Captain America. Fighting Nazis months before the United States entered the Second World War, this hero stood as a counter to Nazi theories of racial superiority, as the product of good old American know-how.

Captain America originally was a frail and weak young man, unfit for military duty, until he was given an experimental serum that transformed him into a super soldier. In a reflection of the egalitarianism of American culture, anyone receiving the same treatment could reach the height of human perfection just as he had. But the secret formula died with the scientist who created it—who was assassinated by a Nazi spy.

At first glance Captain America comes across as an all-American hero, but his story in fact encapsulates the intergenerational experience of immigrants and their children. Growing up in Europe under difficult conditions, immigrants tended to be relatively small of stature, sometimes sickly, while their children, born and raised in the United States, grew up tall and strong due to superior diet and medical care. The powerful resonance of this hero, resurrected by Lee and Kirby a few years into the Marvel Age, continued despite the counterculture movement (Peter Fonda’s character in the 1969 film “Easy Rider” was nicknamed Captain America), and is still present in the sequel to the first Captain America film, in which Scarlett Johansson reprises her role as the superspy Black Widow. “Captain America: The Winter Soldier” continues to remind us of the moral clarity of the American fight against Nazism (in the films largely represented by the fictional organization Hydra), as well as the ideal of the American dream, which tells us that we can improve upon and remake ourselves through our own ingenuity.

The insight about Captain America is not altogether original, in that, for decades now, the character of Superman has been understood to be the ultimate immigrant, but the discussion of Captain America's immigrant connection is a new one.

Anyway, on to the next movie:

Lee and Kirby also created the X-Men, a superhero team composed of mutants, born with genetic differences that resulted in extraordinary powers and abilities. While originally framed as stories about good mutants battling evil mutants, the concept naturally lent itself to stories about prejudice, drawing upon themes derived from the history of anti-Semitism and the Holocaust and the civil rights movement. Magneto, one of the X-Men’s main antagonists, espoused a variation on Nazi racial theories, arguing that mutants constitute a new species, which he dubbed homo superior. Lee and Kirby never intended for the character to be seen as Jewish, although as the back story evolved he was shown to have been a victim of the Nazis, who after all persecuted a number of other minority groups.

Decades after the character was introduced, however, he was transformed into a Jewish-Holocaust-survivor-turned-terrorist through a bit of revisionist comic book history, something of a Malcolm X and Meir Kahane for mutants. In the comics, this depiction is balanced by the presence of other, entirely positive Jewish heroes, such as the young mutant Kitty Pryde, who plays a significant role in “X-Men: Days of Future Past,” but is never identified in regard to religion or ethnicity. That balance is entirely missing in the 2011 film, X-Men: First Class, which shows Magneto’s childhood experiences in a Nazi concentration camp. While this serves to explain his militancy, the transformation from victim to villain cannot be entirely justified, and the characterization would seem to reflect changing attitudes toward Israel and Zionism in recent years. Thankfully, this year’s X-Men film (the seventh in that series) avoids any mention of Magneto’s background, as the future that he and the other heroes fight to prevent is one in which mutants—along with almost everyone else—are subjected to a new kind of holocaust. But there is an obvious bit of relativism at work in this film in that the leader of the anti-mutant crusade is played by Peter Dinklage, a New Jersey native perhaps best known for his work as Tyrion Lannister in Game of Thrones. Although no mention is made of his dwarfism, the clear implication is that even those subject to persecution are not immune from persecuting others.

And since it comes up in the article, here's the trailer for that previous X-Men film:

Embedding is disabled, so we can't include this other video here, but you can watch X-Men Opening Scene (2000) - Magneto in Auschwitz extermination camp over on YouTube, just click away, but be sure to come back here after you're done.

And here is the original comic book cover for the 1981 "Days of Future Past" storyline, featuring older versions of Wolverine and Kitty Pryde:

Now, let 's return to the op-ed for the third Marvel to make it to the silver screen this spring:

Spider-Man is Stan Lee’s most memorable creation, and has been commonly described as Woody Allen with webs, a superhero who is a bit of a schlimazel, plagued with personal problems, perhaps even a bit neurotic, or, in the parlance of the ‘60s, full of hang-ups. Much like Captain America, Spider-Man is described as “puny” before his transformation, in this case due to an accidental bite by a radioactive spider. While meek and mild, he is a highly intelligent and diligent high school student, living with over-protective parents (actually his aunt and uncle), a type familiar enough in postwar Jewish communities like the Forest Hills section of Queens, where the story of Spider-Man begins.

And here's the cover from Spider-Man's 1962 comics debut:

And back now to the opinion piece:

Although he is given an Anglo-Saxon name, Peter Parker, and a matching identity, the Jewish sensibility of Marvel’s most popular hero also extends to his constant use of humor even while fighting a supervillain.

But what drives Spider-Man above all else is a very Jewish sense of guilt. This is worked into his origin. He does not immediately dedicate himself to helping others after gaining his extraordinary gifts. It is only after standing idly by during a robbery that he is shocked to learn that the criminal he allowed to escape went on to murder his Uncle Ben.

Stan Lee’s most memorable quote, “with great power comes great responsibility,” comes via this character, who serves as a father figure for Peter. The Amazing Spider-Man 2 (actually the fifth Spider-Man film, although the sequel to the 2012 series reboot) continues to emphasize the themes of guilt and responsibility as they relate to Peter’s girlfriend Gwen Stacy (another source of tragedy and guilt).

Of course Jews do not have a monopoly on guilt, but we do have our own particular brand of it. A colleague of mine whose father is Jewish and whose mother is Catholic insightfully observed that Catholics make you feel guilty for things that you do, while Jews make you feel guilty for what you don’t do. This of course corresponds to the sins of commission and omission. Ogden Nash, in his poem, “Portrait of the Artist as a Prematurely Old Man,” famously suggested that the sins of commission are preferable in that “they must at least be fun or else you wouldn’t be committing them,” whereas it is the sin of omission “that lays eggs under your skin.”

Speaking of Ogden Nash, here's what you might call the portrait of the poet...

And now for the conclusion of the think piece:

The guilt for what you don’t do, for standing idly by while others suffer, for not taking a stand against discrimination and injustice, for not opposing the evil that we find in the world, for not being the best that we can be and for not taking responsibility for ourselves and for others, is the underlying message of the Marvel Age, in comics and now in motion pictures. It serves as a kind of pop culture midrash for our times.

The Marvel Age of Midrash, that does sound like something Stan Lee might have written, and maybe Jack Kirby too. They did have a taste for alliteration, which maybe had something to do with ancient and medieval Hebrew's use of poetic devices of assonance and parallel structure.

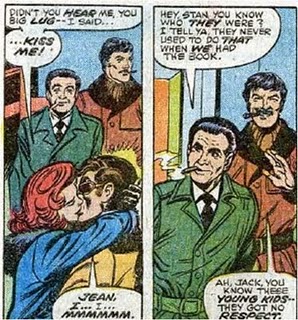

|

| Jack Kirby (l.) & Stan Lee (r.) |

| ||||

| from Uncanny X-Men #98 (1976) |

It's fair to say that Stan Lee, now 91 years old, and Jack Kirby (1917-1994) are the real marvels behind the movies of this past spring. So to Stan Lee, and to the memory of Jack Kirby, we say a hearty, mazel tov!

.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment